Discover more about S&P Global’s offerings

Authors: Evan Gunter – Director, Ratings Performance Analytics, Abby Latour – Editorial Lead, Leveraged Commentary and Data, Joe Maguire – Lead Research Analyst

Research Contributors: Patrick Drury Byrne, Marina Lukatsky (LCD), Matt Carroll, Elizabeth Campbell, Sebnem Caglayan, Ramki Muthukrishan

Published: October 12, 2021

The private debt market has grown tenfold in the past decade with assets under management of funds primarily involved in direct lending surging to $412 billion at end-2020—spurred in part by investors’ search for higher yield.

Borrowers in this market tend to be smaller (averaging $30 million in EBITDA) and more highly leveraged than issuers in the broadly syndicated leveraged loan market—most are unrated.

Transparency and illiquidity are key risks of the growing private debt market; lenders typically lend with the intention of holding the debt to maturity, as private debt loans are often less liquid than broadly syndicated loans.

Despite these risks, private debt appears to have weathered 2020 well, as lenders quickly stepped in with amendments and capital infusions that enabled borrowers to avert bankruptcy, often in exchange for equity.

Private debt has emerged as a new frontier for credit investors in their search for yield, and for borrowers and lenders seeking closer bilateral relationships. The market has grown tenfold in the past decade. The growing investor base, a lack of available data, and the distribution of debt across lending platforms make it hard to know how much risk is in this market—and who holds it.

Listen to a synopsis of this research, read by one of our lead authors.

Assets under management of funds primarily involved in direct lending surged to $412 billion at end-2020—including nearly $150 billion in “dry powder” available to buy additional private debt assets—according to financial-data provider Preqin (see chart 1). This came as institutional investors with a fixed-income allocation (e.g., insurers, pensions, endowments, and sovereign wealth funds) have increasingly waded directly or indirectly into the market. More recently, private debt funds have been marketed as an alternative asset and are increasingly accessible to individual investors through new classes and funds. This expansion of the investor base could lead to heightened risk in the market if it leads to volatile flows of money into and out of the market.

Chart 1: The Market For Corporate Private Debt Has Grown 4x Over The Past Decade

However, as its importance grows, market data is relatively scarce and private debt (also known as direct lending) remains a lesser known corner of finance—with less transparency and liquidity than in the markets for speculative-grade bonds and syndicated loans. While the private debt market is active in both the U.S. and Europe, this report offers a primarily U.S. perspective on the market. While many private-equity-owned issuers are publicly rated and/or funded in the broadly syndicated market, this report focuses on those that rely on private debt from direct lenders. For the purposes of this article we have defined the private debt market as the direct lending market, but acknowledge that a broader definition of private debt could also encompass distressed debt, special situation, and mezzanine debt.

Who Are The Players And What’s The Appeal?

As private debt matured, more lenders emerged. Institutional investors were attracted by the prospect of higher yields relative to other fixed-income assets, higher allocations, quicker execution and expectations for consistent risk-adjusted returns. This increased supply lured borrowers and attracted more private equity sponsors, who were looking for another option to syndicated loans to fund small- to mid-market deals.

This created a business opportunity for private debt providers, including specialty finance companies, business development companies (or BDCs, which were created in the U.S. by an act of Congress in 1980 to provide capital to small and medium-sized borrowers), private debt funds managed by asset managers, collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), mutual funds, insurance companies, and banks. Many of the largest lenders in the private debt market have platforms that encompass several vehicles that hold private debt, enabling private loan deals to grow ever larger.

With more private debt lenders and larger loans available, a growing share of middle-market funding appears to be coming from the private debt market as opposed to broadly syndicated loans. While the number of middle market private equity transactions has remained relatively stable in recent years, the number of broadly syndicated loans in the middle market space has fallen sharply (see chart 2). Assuming private equity sponsors still rely on debt financing to complete acquisitions, one explanation is that middle market private equity sponsors and companies are increasingly turning to private debt markets instead of broadly syndicated markets.

Chart 2.

In general, the private market has grown since the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, given the cost and requirements of being a public company. From the lender’s perspective, leveraged lending guidelines in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2007-2008 led banks to reduce their exposures to risky credits, which provided opportunities for nonbank financial institutions to expand their footprints in the private debt market. Where these guidelines recommended limits of 6x leverage for broadly syndicated loans, leverage levels in private deals may go higher. While these regulatory changes have contributed to the growth of the private debt market over the past decade, regulators in the U.S. are showing growing interest in this asset class as it has grown in size and is reaching a broader base of investors.

More recently, growth in the private debt asset class has been spurred by investors seeking relative value. For example, within BDC portfolios, the nonsyndicated portion of the portfolio had an average spread that was 100 basis points (bps) wider than the broadly syndicated portion in early 2020—although this premium has been shrinking in recent years.

The Borrowers

Borrowers in the private debt market tend to be small to middle-market companies, ranging from $3 million-$100 million in EBITDA. This market is split between the traditional middle market companies (with upwards of $50 million in EBITDA) and the lower middle market (with under $50 million and averaging $15 million-$25 million EBITDA).

While borrowers in the private debt market tend to go without a public rating, S&P Global Ratings assigns credit estimates to nearly 1,400 issuers of private market debt held by middle-market CLOs. A credit estimate is a point-in-time, confidential indication of our likely rating on an unrated entity or instrument, and from this data we can make some broad observations on the market of private borrowers. The average EBITDA for companies on which we have a credit estimate is about $30 million, and the most represented sectors are technology and health care—similar to the rated universe of broadly syndicated loans.

Among private market issuers for which we have credit estimates, more than 90% are private equity sponsor-backed, and these entities tend to be highly leveraged. From 2017-2019, more than 75% of credit estimates had a score of ‘b-’. By contrast, obligors rated ‘B-’ accounted for around 20% of broadly syndicated CLO pools in same period.

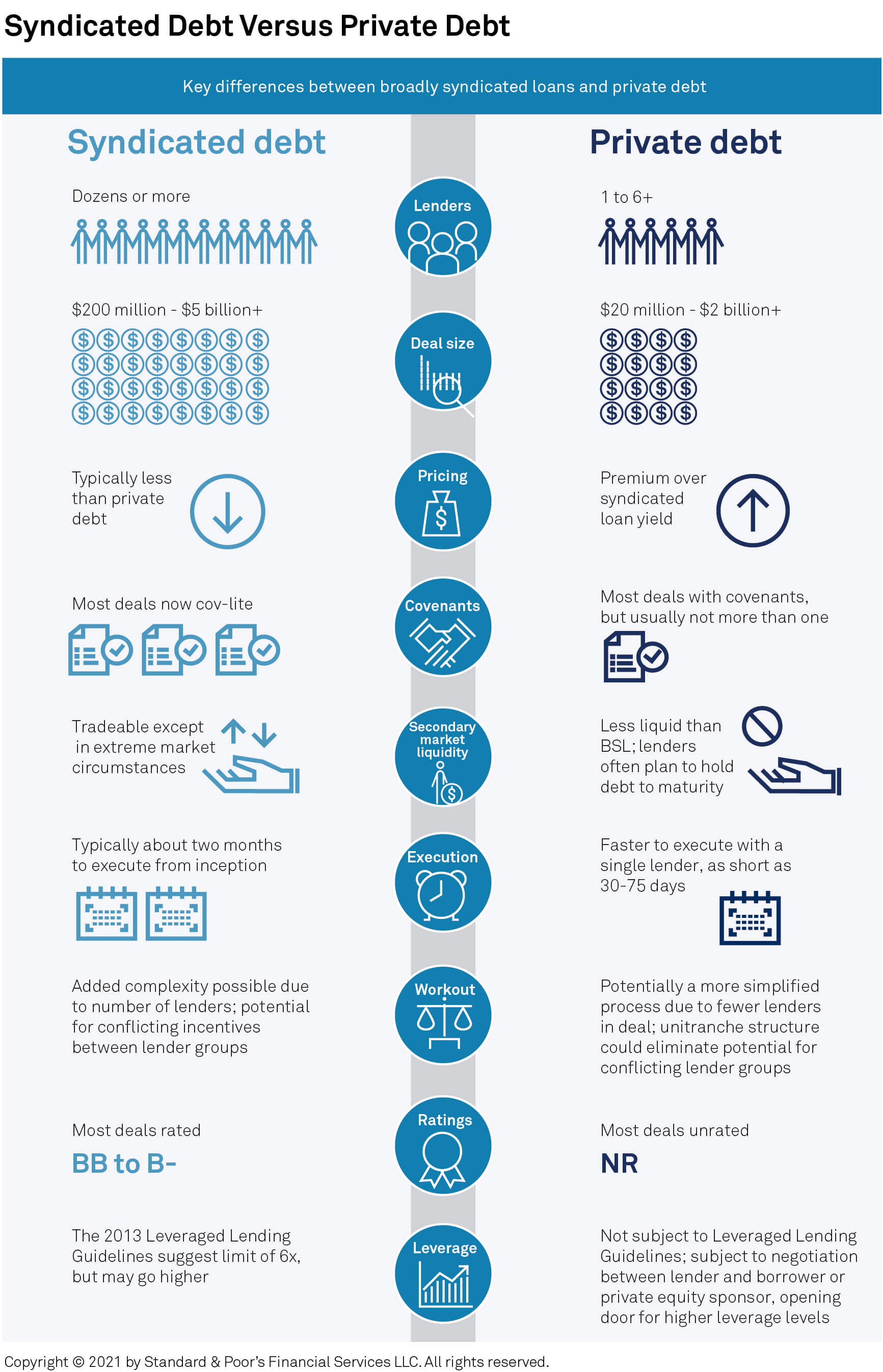

One of the central differences between the private debt market and the broadly syndicated loan market is the number of lenders involved in a transaction. Since private debt deals aren’t syndicated, borrowers work more directly with lenders. On the front end, this allows for quicker turnaround (about two months from inception to execution), and borrowers also know the pricing through their direct negotiation with the lender, instead of submitting to the syndicate market’s shifting conditions. Unlike in the broadly syndicated loan market, covenants are still written into most private loan agreements. For firms that face liquidity needs and are otherwise unable to access the public capital markets, private debt has a reputation as “bear market capital” available during periods of market stress—but at a price.

In 2020, many middle-market companies were at risk of breaching financial maintenance covenants with financial positions under pressure. Many private lenders quickly stepped-in with amendments that helped borrowers meet immediate liquidity needs. These amendments included agreements such as capital infusions, switching cash interest owed to payment-in-kind, and postponing amortization schedules that we viewed as distressed exchanges. While these transactions contributed to the elevated number of selective defaults of middle market companies during the year, they also helped to avert payment defaults, in exchange for increased equity stakes to the lender.

In the second quarter of 2020, private loan defaults in the U.S. peaked at 8.1%, according to the Proskauer Private Credit Default Index. Our universe of credit estimates showed a similar default rate of 8.4% (including selective defaults) in June 2020. Excluding selective defaults, the credit estimate default rate was lower than that of the broadly syndicated S&P Global Ratings/LSTA Leveraged Loan Index, which also excludes selective defaults. (see chart 3).

Chart 3

The Lenders

Asset managers—especially alternative asset managers—are central to the private debt market through their lending platforms. It’s not unusual for asset managers to operate lending platforms that include multiple lending vehicles, BDCs, private debt funds, middle-market CLOs, and mutual funds, thus enabling them to gradually offer ever-larger loans. Loans originated by a BDC in the lending platform may be distributed to the private debt funds, or middle-market CLOs that are managed by the same institution. With exemptive relief from the SEC, the asset manager may co-invest alongside the BDC and the private debt vehicle in the same deal, resulting in larger pieces of the deal for the same asset manager. Through its lending platform, an asset manager can allocate a loan across several of its managed vehicles, which are frequently enhanced by leverage.

Recently, we’ve seen further pairings between alternative asset managers and insurers, where the insurance company can provide a source of perpetual capital for the lending platform. Alternative asset managers place illiquid credit assets in the buy-and-hold portfolios of insurers to earn the illiquidity premium. For example, asset manager Apollo Global Management Inc. manages substantially all of annuity provider Athene Holding Ltd.’s assets, and these assets represent a significant share (around 40%) of Apollo’s assets under management. Earlier this year, Apollo announced its plan to merge with Athene.

While private debt funds have been targeted mostly toward institutional investors, several large asset managers have recently taken steps to open classes of private debt funds to accredited individual investors. As private debt has traditionally been a buy-and-hold asset, it may seem ill-suited as an asset in a redemption-eligible fund. However, this risk could be mitigated if the fund has sufficient safeguards in place that could prevent investor redemptions from leading to forced sales of illiquid private debt.

Whether independent or operating as part of a larger lending platform, BDCs are central players in the private credit market as direct lending is their core business. As BDC lending tends to be highly concentrated in the private credit market, public ratings on BDCs can provide a narrow view into this private market. While most of the BDCs that we cover are rated 'BBB-', many are relatively large with relatively good underwriting track records; smaller BDCs as well as those with more mixed underwriting records tend to go unrated.

A traditional strategy of private credit lenders has been providing first-lien term loans to middle-market companies backed by private-equity sponsors. This area has arguably come to define private debt’s core business. This core business is evolving, with some lenders championing “unitranche” structures that eliminate the complex capital structure of first- and second-lien debt in favor of a single facility. The unitranche structure typically features a higher yield than a syndicated first-lien loan, typically commanding a premium of 50-100 bps over traditional senior financings to compensate lenders for increased risk. However, it may offer borrowers a lower average cost of capital over the entire debt structure.

What Are The Attractions and Risks Of Private Debt?

Closer Relationship Between Lender and Borrower: Private debt remains very relationship-driven. With fewer lenders involved in a single transaction, borrowers tend to work more closely with their private debt lenders. Borrowers can benefit as deals can be executed more quickly, and with more certainty of pricing, than with a large syndicate of lenders. Furthermore, the speed at which amendments were struck in the private debt markets as the pandemic unfolded highlights this relationship.

Use Of Covenants: Private debt is a corner of the loan market where covenants are still common. Most deals have at least one, and this provides some protection for the lender. For example, a significant portion of the companies for which we do credit estimates have financial-maintenance covenants. However, the presence of covenants does appear to contribute to more frequent defaults (particularly selective defaults) and workouts of private borrowers (as we saw with the spike in selective defaults in 2020).

Post-Default Workouts: With fewer lenders, the process of working out a debt structure in the event of a default tends to be faster and less costly for a private borrower. Furthermore, simpler debt structures (such as unitranche deals) remove the complexity of competing debt classes that can slow a restructuring. These factors contribute to recovery rates for private debt that are often higher on average than those on broadly syndicated loans.

Illiquidity: This is a key risk of private debt, as these instruments typically are not traded in a secondary market—although this may change over time if the market in terms of volume and number of participants continues to grow. Because of this, there is limited market discovery and lenders must often approach the market with the willingness and ability to hold the debt to maturity. For example, buyers of private debt include life insurers that are well-positioned to take on the liquidity risk of this debt with the buy-and-hold nature of the portfolios. Meanwhile, private debt funds geared toward individual investors may pose a risk if they are vulnerable to redemptions that could cascade to forced asset sales. Private debt’s illiquidity could complicate matters for an investor seeking a hasty exit.

Weaker Credit quality: Private debt borrowers tend to be smaller, generally with weaker credit profiles than speculative-grade companies. Based on the sample of private debt borrowers for which with have credit estimates, these issuers are even more highly concentrated at the lower end of the credit spectrum than are speculative-grade ratings broadly. Near the end of last year, close to 90% of credit estimates were ‘b-’ or lower, including nearly 20% that were ‘ccc+’ or below. At the time, 42% of U.S. spec-grade nonfinancial companies were rated ‘B-’ or lower, with about 17% rated ‘CCC+’ or lower (see chart 4). However, as highlighted above, private debt performed solidly at the outset of the pandemic, exhibiting a lower default rate than the comparable leveraged loan index.

Furthermore, aggressive growth in private debt has led to a decline in the quality of underwriting in recent years. As in the broadly syndicated market, we’re seeing increased EBITDA add-backs. In the loan documentation, the definition of EBITDA is getting longer and less straightforward, becoming more similar to the definitions used in broadly syndicated deals. There are also some signs of covenant erosion, particularly among larger private loans.

Chart 4

Credit Estimate vs. U.S. Spec-Grade: Relative Credit Quality

Limited Visibility: By definition, less information is available on private debt than on public debt. Furthermore, the close relationship between lenders and borrowers (and the smaller pool of lenders in a deal) means that while sufficient data exists for lenders to approve and execute individual transactions, fewer are privy to the details. As a result, we know less about the aggregate size and composition of the overall market. Furthermore, the distribution of the private loans within lending platforms involving BDCs, private credit funds, and middle-market CLOs make it difficult to track the level of risk in this market, and who ultimately holds the risk.

Private Debt: A New Target In The Hunt For Yield

With investor hunt for yield unlikely to diminish, the private debt market looks poised to add to its recent explosive growth. Given the steady track record of performance and attractive returns for this sector over the past decade, and spreads on offer that are typically wider than those for broadly syndicated loans, it’s no surprise that institutional (and perhaps individual) investors are ramping up demand for private debt.

This, of course, carries some risk. Private debt borrowers tend to be smaller and more highly leveraged than issuers of syndicated loans, and transparency into this market is clouded as the private debt borrowers are mostly unrated. Adding to this risk, the market’s expansion has led to a decline in the quality of underwriting, while lenders must typically be able to hold the debt to maturity, given that these instruments are less liquid than broadly syndicated leveraged loans.

Regardless, the appeal of the market to lenders and borrowers alike suggests that what has been a little-seen corner of finance is stepping into the spotlight.

Related Research: