As the U.S.-China trade dispute intensifies further--so has credit risk. The negative credit impact of the conflict on corporate issuers has been modest so far, as companies have largely passed on the cost of tariffs to consumers and the dispute had largely been contained to retaliatory tariffs on intermediate inputs. But this could soon change: the U.S. has announced its intention to place tariffs of 25% on any imports from China that have not yet been subjected to levies--about $300 billion worth--including smartphones and laptops, apparel and footwear, and toys, which would directly hit consumers. In addition, non-tariff measures are becoming more prevalent, though it's not the first time they've been used. The U.S. has imposed export restrictions on Huawei, prompting China to announce an "entity list" of its own, hint at an export ban of rare earth minerals and launch an investigation of FedEx.

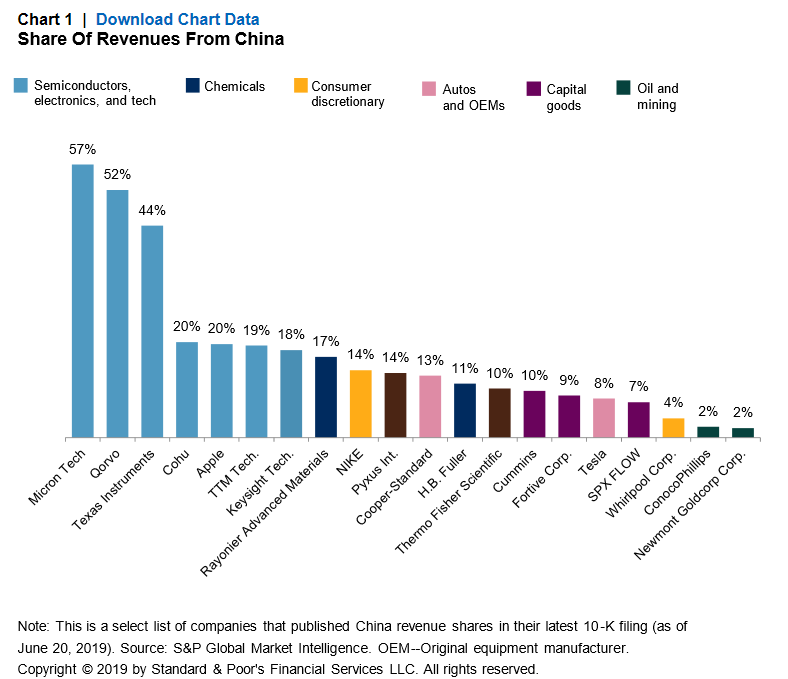

We expect the next rounds of escalation to amplify both profit pressures and uncertainty. With 25% levies on all imports from China (worth $540 billion in 2018), it may become more difficult to continue passing on costs to consumers and companies may need to absorb a bigger share of the tariff costs. Meanwhile, non-tariff actions and their effects are more unpredictable, often targeting specific companies or sectors, and can directly affect revenues (as in Huawei's case). While companies have mitigated tariff risks by passing on costs and adjusting supply chains to an extent (companies have also had some time to prepare for higher tariffs), they could find it more challenging to respond to non-tariff measures. Some U.S. corporates have significant revenue exposure to China and are vulnerable to consumer boycotts or buying and selling restrictions. These companies range from large, highly rated companies like Apple, for whom China accounts for $50 billion or 20% of total revenues, to small lower-rated issuers like tobacco company Pyxus International, which generates 14% of its revenues in China (see chart 1).

A resilient U.S. economy has helped corporates weather the U.S.-China dispute, but this support is now shakier due to weaker growth prospects. S&P Global Ratings economists believe that the tariffs that the U.S. and China have levied on each other's products will have minimal direct impacts on both countries; however, if the disputes begin to erode confidence and tighten financial conditions, the impact on the overall economy and creditworthiness will be more damaging. Lower aggregate demand would also hit industries not directly in the crossfire of the trade war and the dollar would strengthen further, adding to earnings pressure.

The U.S. and China may well come to some agreement and avoid further escalation; President Trump and President Xi Jinping are expected meet at the G-20 meeting on June 28 and 29, which could break the current impasse. But there's also the risk that, even without escalation, a standoff would lead to an extended period of uncertainty and long-lasting damage to the economic ties between the two nations. For many U.S. corporates, this would limit long-term growth prospects since China remains a key market and growth opportunity.

Latest Escalation Has Raised Costs And Uncertainty

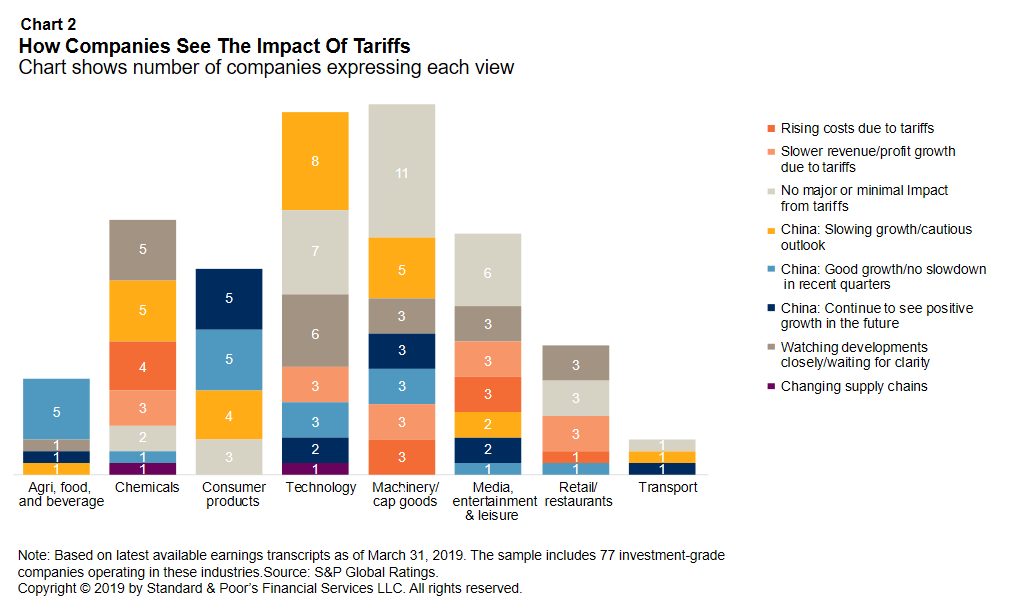

We see more downside credit risk in the next rounds of escalation. Auto original equipment manufacturers and suppliers, capital goods, consumer products, retail, and technology companies could feel more pressure because of their relatively higher input cost exposure to China and, in some cases, limited ability to pass on increased costs from tariffs. Many are vulnerable to retaliation from China. The U.S. farm sector has borne the brunt of China's retaliation, and its suppliers (e.g. agriculture equipment manufacturers) will continue to face the negative repercussions. Some agribusinesses have actually benefited from lower agricultural prices, and some products targeted by China were diverted to other markets. Our analysis of first-quarter earnings transcripts of investment-grade companies in select sectors (before the escalation in May) shows that, in addition to higher costs, U.S. issuers see slower profit growth and are concerned with both China's growth and the uncertainty stemming from the tariff wars (see chart 2).

So far, companies have mostly been able to pass on higher costs from levies to customers or consumers. The cost impact may not have actually been as large as the tariff rate suggested. The past tariff rounds--namely the 10% rate on $200 billion of Chinese goods--was not particularly steep or they applied to low-cost intermediate inputs, which often represent a small portion of a company's total costs. But the next tariff round will likely be more harmful. For instance, a 25% levy on iPhones could raise their price by about 15%, which we believe Apple would not be able to fully pass on to consumers.

Currency movements also offset some of the tariff's impact because the Chinese currency weakened 10% against the dollar from March 2018 when the first tariff plans were announced to the November 2018 "truce". In fact, the dollar strengthened overall, which likely reduced the cost of imported inputs from other countries. Our economists believe China is likely tolerate more flexibility versus the dollar so long as the moves are not too large and do not trigger destabilizing capital outflows.

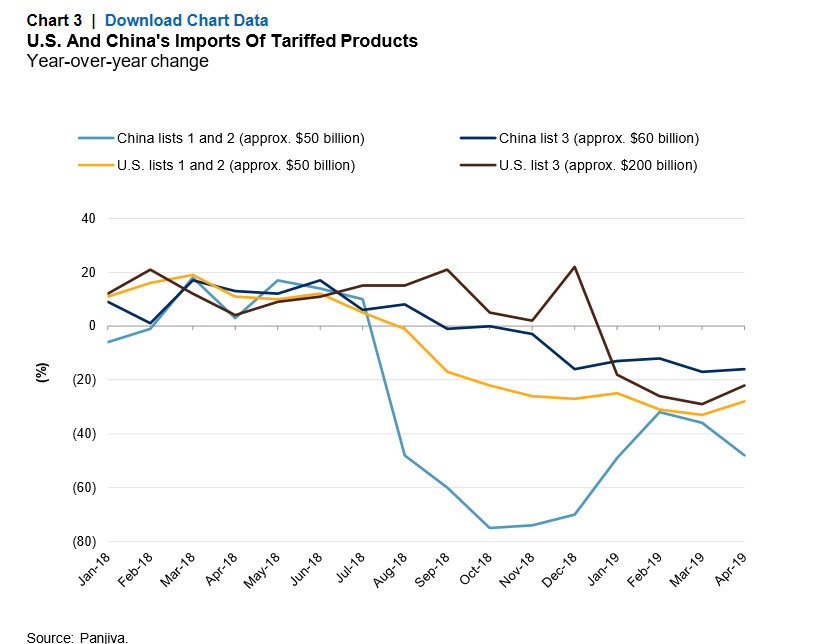

Bilateral Trade Between The U.S. And China Is Down

While the retaliatory tariffs have reduced trade between the U.S. and China, we expect that this latest tariff hike and the planned expansion of levies to all Chinese products will only continue that trend. Since import levies were first applied in the middle of 2018, the U.S. and China's imports from each other have been falling, with the largest declines seen in China's product tariff lists (one and two), which mainly targeted U.S. commodities (see chart 3). What's more, even some Chinese imports that had yet to be subjected to tariffs also decreased because companies began diverting trade in response to supply chain risks.

As Tensions Continue, Companies Are Shifting Supply Chains

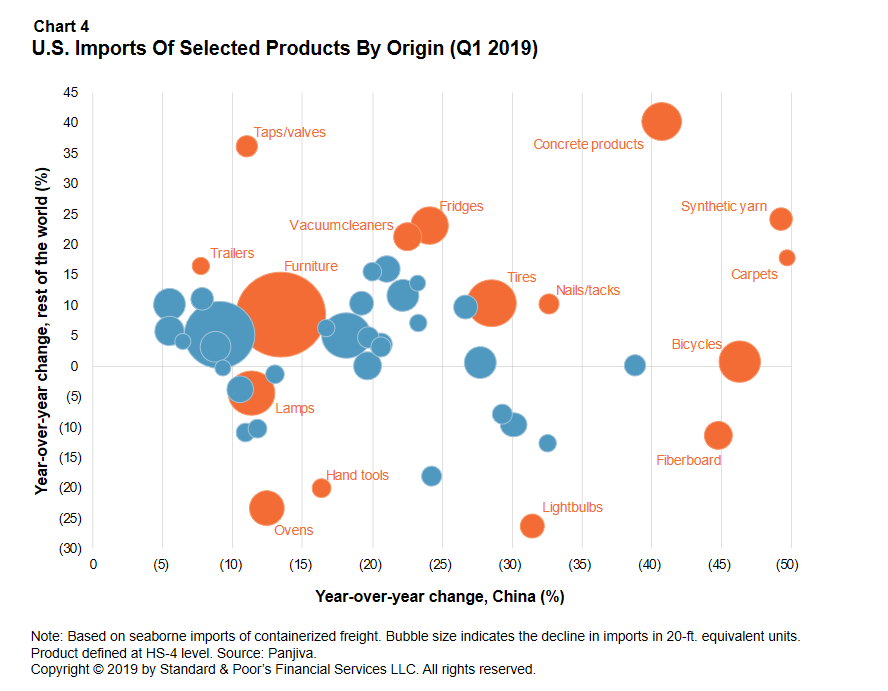

We have begun to see imports from China be substituted with products from elsewhere. The U.S. has reduced its purchases of some of the Chinese products that have been subject to levies, while buying more from the rest of the world (see chart 4). Companies are sourcing more from other countries--notably India, Malaysia, South Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam--where a production footprint already exists. Mexico also stands to benefit from the trend toward sourcing and producing closer to market because of its proximity to the U.S.

We think U.S. companies will continue to optimize their supply chains and divert away from China. However, this strategy is not costless. It's limited by near-term capacity constraints and will be more challenging for sectors that require skilled labor and high-value manufacturing. It is very difficult to replicate China's well-developed and integrated technology supply chain elsewhere. In addition, China itself is a large market for technology products and technology companies may want to continue manufacturing near it. All in all, companies have been able to mitigate the impact of past tariffs by passing on increased costs, diverting trade, and adjusting their supply chains. But as the U.S.-China dispute escalates, its costs will pile up, leaving less room for near-term mitigation strategies and increasing its adverse credit effects.